A Newer Era of Networked Science

“Imagine a world in which every human being can freely share in the sum of all knowledge…” (Wikipedia’s vision statement)

“A fact of any scientist’s life is that you carry a lot of unsolved problems around in your head. Some of those problems are big (“find a quantum theory of gravity”), some of them are small (“where’d that damned minus sign disappear in my calculation?”), but all are grist for future progress. Mostly, it’s up to you to solve those problems yourself. If you’re lucky, you might also have a few supportive colleagues who can sometimes help you out.

Very occasionally, though, you’ll solve a problem in a completely different way. You’ll be chatting with a new acquaintance, when one of your problems (or something related) comes up. You’re chatting away when all of a sudden, BANG, you realize that this is just the right person to be talking to. Maybe they can just outright solve your problem. Or maybe they give you some crucial insight that provides the momentum needed to vanquish the problem.

Every working scientist recognizes this type of fortuitous serendipitous interaction. The problem is that they occur too rarely.

A few years ago, I started participating in various open source forums. Over time, I noticed something surprising going on in the healthiest of those forums. When people had a problem that was bugging them, rather than keeping silent about it, they’d post a description of the problem to the forum. Often, I’d look at their question and think to myself “yeah, I can see why they posted, that looks like a tough problem.” Then, forty minutes later, someone would come in and say “Oh, that’s easy, you just do X, Y, and Z”. Very often, X, Y and Z were quite ingenious, or at the least relied on knowledge that neither I nor the original questioner possessed. The original problem had been trivial all along.

What’s going on is similar to the fortuitous scientific exchange. A problem that’s difficult or impossible for most people can be trivial or routine to just the right person.“ - Michael Nielsen

Throughout the 1930s and ‘40s mathematicians from the Lwów School of Mathematics would meet at a nearby café to discuss and collaborate on research problems- scribbling their thoughts and ideas on the café’s marble Stammtisch tabletops to think through and collaborate on problems.12

To keep the results from being lost to time, and after becoming annoyed with the mathematicians writing directly on the tables, Stefan Banach's wife, Łucja (Lucy), provided the mathematicians with a large notebook to write down these problems to either potentially try and solve, or refute in future discussions. This book—a collection of solved, unsolved, and even probably unsolvable problems—could be borrowed by any of the guests of the café, and over the years would accumulate almost 200 problems. In effect, this led to the founding of new fields of mathematics and became known as the Scottish Book— named after the coffeehouse where they convened.3

For problems that seemed especially important or difficult, the problem's proposer would often pledge a prize for its solution, such as beer or wine.

In November 1936, Stanislaw Mazur posed a problem on representing continuous functions. Formally written down as Problem 153, Mazur promised a live goose, (an especially rich prize during the Great Depression), as a reward if someone could find a solution. 36 years passed before someone finally managed to find a (negative) solution, and, in keeping with the conditions of the book, Per Enflo, in a ceremony broadcast throughout all of Poland, was awarded his live goose by the man who initially proposed the problem.

Where are today’s Scottish books— databases of open questions that researchers can stumble across, read, and collaborate on, or ideas that entrepreneurs can invent.?4

Patrick Collison, Gwern, Tyler Cowen, Luke Muehlhauser, Sam Enright, Fin Moorhouse, Alexey Guzey, Logan Graham, Open Philanthropy and the Institute of Progress, have all written some fine examples of questions they want answered and projects created. But where else do these exist?

Why aren’t university departments compiling databases of research questions that students and academics are interested in, but can’t answer by themselves? These needn’t be subject-specific. In fact, it would be better if they weren’t. Some of the most interesting research on AI, for example, doesn’t come from computer scientists, but from linguists and neuroscientists.56 How much more knowledge is hidden away because the major breakthroughs come from disparate pathways? Pathways that no one would ever consider thinking about?

If we take one of the above questions at random, say: “How does the subjective perception of time vary across species?”, economists working on temporal discounting might be interested. So too might animal behaviourists. Maybe also psychologists working on consciousness. And philosophers on sentience. Compiling a Modern Scottish Book would allow all these different researchers to work together, and potentially make a breakthrough when typically they would not interact.

Could Large Language Models help with this: by opening up possible unexplored avenues for collaboration and allow us to target the question to those who have the knowledge but wouldn’t typically interact with the problem?7

Whilst it’s understandable that perverse incentives dissuade academics—who are often fighting for tenure or funding— from openly disclosing potential research questions, this is, however, to the detriment of scientific discovery and human progress.8 If we want to develop, we must change the incentives. How many questions are in the heads of scientists: questions that they keep to themselves because they can’t answer, but someone else can? How many of these will be forgotten or lost to time?9 How many offshoots could these spurt, and how many new fields could they potentially discover?10 How much human progress is lost as a result?11

To try and encourage more people to openly publish their research questions, ideas and projects, I am openly disclosing my own. Please have a look, comment, share and build. Here’s my list.

"The destiny of computers is to become interactive intellectual amplifiers for all humans, pervasively networked world-wide." - Alan Kay/Licklider12

Addendum

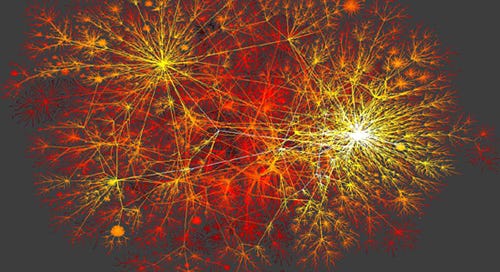

Over one million articles are published every year in biomedicine and life sciences, so it’s very difficult to track the evolution of publishing over time, and near impossible for a human to do it unaided. So, last year Nomic and Tübingen University decided to try and do something about it and trained an LLM on >21 million PubMed articles. In doing so, they created an interactive bibliometric map to represent the entire biomedicine field.

This tool helps researchers visualise where potential breakthroughs may come about, and how certain fields in biomedicine grow or shrink over time.13

The map is also filterable- allowing us to see authors’ gender, retractions, and citation counts by subfield, potentially helping us understand blindspots in research.1415 This is the best example of using AI to aid collaboration I’ve seen: could we create something similar to aid collaboration between researchers?

Since writing this, students at Stanford have built an open discussion forum for ArXiv papers. A very good way for researchers to discuss ideas with one another [Source].

Further Reading

Amateur Hour: A Thinking Guide For Independent Researchers (And Academics Thinking Independently) - A very interesting article looking at how amateurs bring about breakthroughs in science, and the barriers they face. Much of this is interchangeable with my article about LLMs.

Hoare, G. T. Q. (1999), Obituary: Stanisław Ulam 1909-1984, The Mathematical Gazette, Vol. 83, Issue 496, pp10–24.

Lakens, D., and Ensinck, E., (2024), Make Abandoned Research Publicly Available, Nature Human Behaviour- Ironically, this paper is behind a paywall. This was outwith the authors’ control. They’ve made a preprint available here.

MacTutor, (2002), The Scottish Book - A brief history of the Scottish Book

Nielsen, M., (2012), Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science- The ultimate guide to metascience. I highly recommend reading.

Metascience of the Vesuvius Challenge by Maxwell Tabarrok - An interesting look into how ‘nerd sniping’ developed the Vesuvius Challenge.

Zielinski, C., (2019), Mathematicians at the Scottish Café, IFIP International Conference on the History of Computing, pp 252-275. - A more in depth history of the Scottish Café, written by the café owner’s grandson, Chris.

Matt Clancy (of the excellent New Things Under the Sun Blog), has written a very good literature review looking at whether Twitter can boost research impact by improving serendipitous interactions.

To summarise the article, there is both evidence that Twitter may and may not increase research outreach and citation count. He concludes further investigation is required, and makes specific mention of citations being a poor metric for understanding impact.

In nearby Hungary, the plein-air Nagybánya- a group of Hungarian painters, sculptors, and architects, were doing very much the same thing: scribbling on the raspberry-coloured marble surfaces at The Japan Café. [Source: Lukacs, J., (1994), Budapest 1900.]

“What is striking[…] is the amazing density and diversity of culture that filled the space. There were completely parallel universes operating in the same room, and evidently at the same time[…] While the mathematicians were contemplating Banach spaces at one table, speaking in sudden bursts and sketching geometric shapes on the table tops, Roman Jaworski and his friends were conducting regular sessions of the Constructivists’ Club at another […] The Café was throbbing with intelligence. Near to the mathematicians, another table united the philosophers and logicians. These were led by Kazimierz Twardowski, the founder of the Lwów-Warsaw school of logic, who used the Café as an office, writing his philosophical works here, and holding professional discussions with colleagues […] There was the painter-philosopher Leon Chwistek; Jan Łukasiewicz, who among his other pursuits in logic invented Polish and Reverse Polish Notation, which are still being used in computer science and calculating machines; and Alfred Tarski […] Journalists scribbled at the tables – including Bruno Winawer, who wrote his popular socio-scientific comedies and columns on science and literature here.” [Source: Zielinski, 2019]

Here are some examples of practical applications of Lwów mathematics:

Banach spaces- used in spacecraft and missile trajectory planning

Game theory and the Monte Carlo method

Number theory

The Kaczmarz method provides the basis for many modern imaging technologies, including the CAT scan.

Stanisław Ulam recollects these café sessions as being incredibly productive:

“Collaboration was on a scale and with an intensity I have never seen surpassed, equaled or approximated anywhere - except perhaps at Los Alamos during the war years…Needless to say such mathematical discussions were interspersed with a great deal of talk about science in general (especially physics and astronomy), university gossip, politics, the state of affairs in Poland: or to use one of John von Neumann’s favourite expressions, the ‘rest of the universe’. The shadow of coming events, of Hitler’s rise in Germany and the premonition of a world war loomed ominously” - Ulam

“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeing new sights, but in having new eyes” - Marcel Proust

See: Science is Getting Less Bang For Its Buck by Michael Nielsen and Patrick Collison.

“In the evenings, as the customers were shooed away, the tables [at the Scottish Café] were often wiped down and the chairs placed upside down on them so the floor could be swept as well. One can only imagine the agonized faces of the mathematicians coming back the next day to continue their theoretical work only to find it had been washed away by an industrious cleaner. Some were saved by the intercession of the owner.

A partial solution was introduced. According to Urbanek, after one of Banach’s major evening bursts of mathematical genius had vanished by the next morning, ”One day Professor Lomnicki came in….and said that if this happens again, to, please, always leave the writing on the table as it is and store the table somewhere until the next day.” So the scribbled on tables were covered with a cloth and set aside. The cleaners who came in the morning were told that such tables should not be washed, and around 11 o’clock a student would come in and transcribed the mess onto paper. This process worked, at a pinch, but it made nobody happy.” [Source: Zielinski, 2019]

This is similar to the file drawer problem. Not all studies that scientists perform end up being published. [See Lakens and Ensinck, 2024]

It was at the Scottish Café that Ulam claims Mazur proposed the first examples of infinite mathematical games, and sometime in 1929 or 1930 raised the question of the existence of automata which would be able to replicate themselves, given a supply of some inert material:

“We discussed this very abstractly, and some of the thoughts which we never recorded were actually precursors of theories like that of von Neumann's on abstract automata.” [Cited in Zielinski, 2019, from Ulam’s Adventures of a Mathematician]

It’s documented that, at least on one occasion, John von Neumann visited the Scottish Café:

“Banach and other mathematicians got von Neumann so drunk on vodka that he had to leave the table to visit the toilets; but he came back and continued the mathematical discussion without having lost the ability to reason.” [Source]

The authors found that:

“Early papers focussing on COVID-19 were predominantly clinical, while research on societal implications and vaccine hesitancy only appeared later. Similarly, neuroscience originated as a study of cellular and molecular mechanisms, and later broadened to include behavioural and computational research.”

It would be interesting to see how paradigm shifts come about in other disciplines.

Out of 443 retractions, 48 had the title structure: “MicroRNA-X does Y by targeting Z in osteosarcoma.”

The authors found that 24 out of these 25 authors were affiliated with Chinese hospitals, and, therefore, believe that paper milling and perverse incentives focussing on publishing rather than research, are to blame.